Updated: 12/30/2023

Autonomic Nervous System – Dysfunctional?

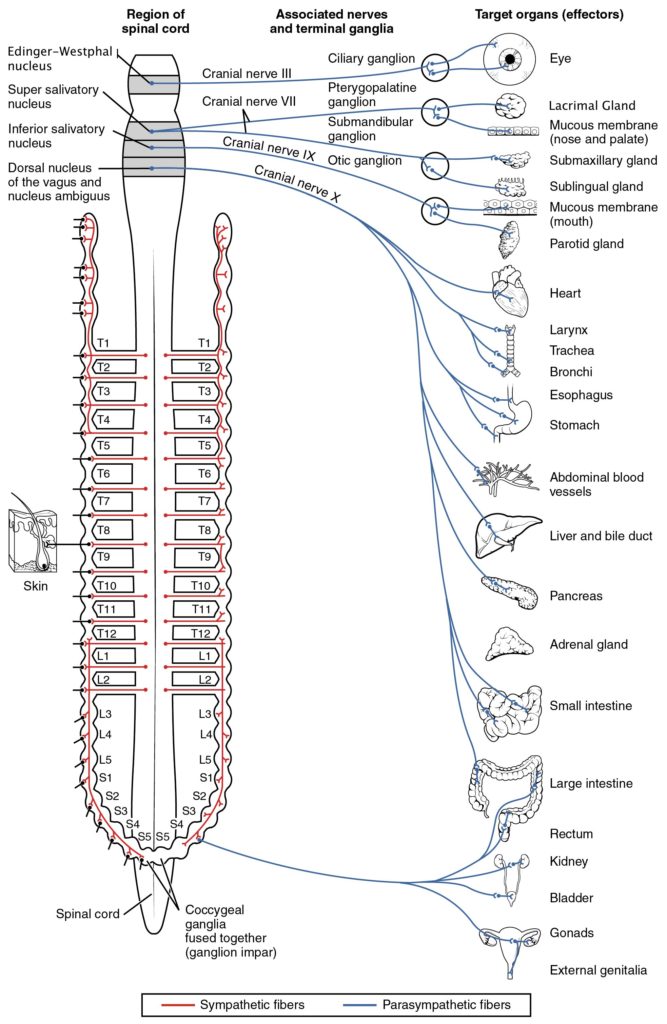

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) plays a pivotal role in regulating our body’s involuntary functions, including heart rate, digestion, and respiratory rate. Dysautonomia refers to a group of conditions that cause a malfunction of the ANS. Understanding how the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems operate is crucial in comprehending dysautonomia.

The Sympathetic vs. Parasympathetic Nervous System

The ANS is divided into two major components: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The SNS is often referred to as the ‘fight or flight’ response, activating during perceived threats, increasing heart rate, and redirecting blood flow towards essential organs (1). Conversely, the PNS is known as the ‘rest and digest’ system, promoting calming and restorative processes (2).

Dysautonomia: When the ANS Goes Awry

Dysautonomia manifests when there is an imbalance between the SNS and PNS, leading to various symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue, and gastrointestinal issues (3). This imbalance can be due to a multitude of factors, including genetic predisposition (4).

Physical Effects of ANS Dysfunction

Peripheral neuropathy, a common outcome of dysautonomia, can lead to decreased nerve control, resulting in symptoms like reduced sweating and dry skin (5). The heart, being significantly influenced by the ANS, can exhibit abnormal rhythms and rates, contributing to the complexity of dysautonomia (6).

The Brain’s Role

The human brain, including regions like the cortex and cerebellum, plays a critical role in regulating the ANS. Dysfunctions in these areas can lead to exaggerated responses from either the SNS or PNS, exacerbating dysautonomia symptoms (7).

The Risks of a Dysfunctional ANS

Chronic stress, a significant trigger for dysautonomia, can lead to serious health issues, including hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (8). Emotional stress, in particular, has been linked to hypertension, one of the common conditions associated with dysautonomia (9).

Treatment for dysautonomia varies but often includes addressing the underlying cause, such as managing stress or treating peripheral neuropathy. Non-pharmacological approaches, including stress management techniques like the Hof Method, can be beneficial (10). Medications may also be prescribed to manage symptoms, although their effectiveness can vary.

Understanding your body’s response to stress and taking steps to mitigate it, such as regular exercise and relaxation techniques, is crucial in managing dysautonomia. A holistic approach, incorporating both physical and emotional well-being, is often the most effective strategy in dealing with this complex condition.

Conclusion

Dysautonomia, a disorder of the Autonomic Nervous System, poses challenges due to its impact on various bodily functions. By understanding the roles of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, individuals can better comprehend the symptoms and seek appropriate treatments. Managing stress, both physical and emotional, is key to mitigating the effects of this condition.

References

- Goldstein, D. S. (2011). “The Autonomic Nervous System in Health and Disease.” Neurologic Clinics, 29(2), 295–317.

- Benarroch, E. E. (1993). “The Central Autonomic Network: Functional Organization, Dysfunction, and Perspective.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 68(10), 988–1001.

- Freeman, R., et al. (2011). “Consensus Statement on the Definition of Orthostatic Hypotension, Neurally Mediated Syncope and the Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Clinical Autonomic Research, 21(2), 69–72.

- Shibao, C., et al. (2005). “Genetic Aspects of Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Circulation, 111(8), 1056–1061.

- Zilliox, L. (2017). “Clinical Evaluation and Management of Peripheral Neuropathy in Diabetes.” Diabetes Spectrum, 30(2), 108–117.

- Vinik, A. I., et al. (2003). “Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy.” Diabetes Care, 26(5), 1553–1579.

- Critchley, H. D., & Harrison, N. A. (2013). “Visceral Influences on Brain and Behavior.” Neuron, 77(4), 624–638.

- Kivimäki, M., & Steptoe, A. (2018). “Effects of Stress on the Development and Progression of Cardiovascular Disease.” Nature Reviews Cardiology, 15(4), 215–229.

- Esler, M., & Kaye, D. (2000). “Sympathetic Nervous System Activation in Essential Hypertension, Cardiac Failure and Psychosomatic Heart Disease.” Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 35(7 Suppl 4), S1–7.

- van Middendorp, H., et al. (2014). “The Hof Method: A Controlled Study of a Novel Stress Reduction Method.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(5), 361–367.

The spinal cord is the principal cable whereby incoming and outgoing messages flow.